ARMALITE AR-10

TO READ THIS ARTICLE IN ITALIAN CLICK HERE

From Aeronautic to the “Tomorrow Rifle”

The Second World War had ended, and the World moved into the fifties, but the technological progress brought about by the conflict didn’t there. Especially in the military field, as well as those in aerospace and chemistry. New alloys, chemicals as well as new production techniques were developed in order to produce lighter and stronger materials. It was at this moment that the ideas of engineers like George Sullivan, who had been working for Lockheed Aircraft Corp were met with open arms: a new ultra light rifle.

It was built with the German concept of an individual multi-purpose infantry rifle in mind; using an alloy mix of steel and aluminum, but also fiberglass and plastic were used although to a lesser extent. This could allow to standardize the infantry with a firearm that could fill many roles.

In 1953 Sullivan was able to meet and talk with one of the managers of the Fairchild Engine and Airplanes Corporation – another business involved in the aeronautic filed and the production of aluminum components based in Maryland.- This allowed him to bring his idea to the attention of the head of the business, Richard S. Boutelle. Sullivan was lucky not only because Boutelle was a firearm and hunting enthusiast, but also because he was looking to differentiate his company’s production whilst attempting to expand into new markets. So in October 1954 ArmaLiteDivision was born. It was a Fairchild’s branch based in Hollywood, where Sullivan had already invested in a small enterprise along with a business partner of his. Sullivan then gathered a team hiring his brother in law, Charles Dorchester, who had already designed a rifle before. He also hired Eugene M. Stoner - an Army Ordnance technician – as the chief engineer.

Left: AR-1 / Right: AR-5

Left: AR-1 / Right: AR-5

Sullivan and Dorchester developed the first firearm, the AR-1, in which AR stood for Armalite Rifle. It was, basically, a manually operated bolt action carbine with an aluminum receiver and a fiber glass stock, chambered in 308 Winchester. The AR-1 wasn’t a success and only a few rifles were made.

In the two following years ArmaLite came up with a few successful designs: one of those was the AR-5, a bolt action rifle in .22 Hornet that the US Air Force will adopt as a survival rifle for the pilots under the name of MA-1. Next were the AR-3 and the AR-9, both firearms made use of the same gas tube and multi-lug rotating bolt that will be seen in the AR-10 and the AR-15. The concept of a eight-lugged rotating bolt, that closes on the barrel extension, was not the brainchild of Eugene Stoner himself, as many thinks today, but was the contribution of Melvin M. Johnson Jr.. Johnson was collaborating with ArmaLite because his company, the Johnson Automatics Manufacturing Company, was in financial troubles.

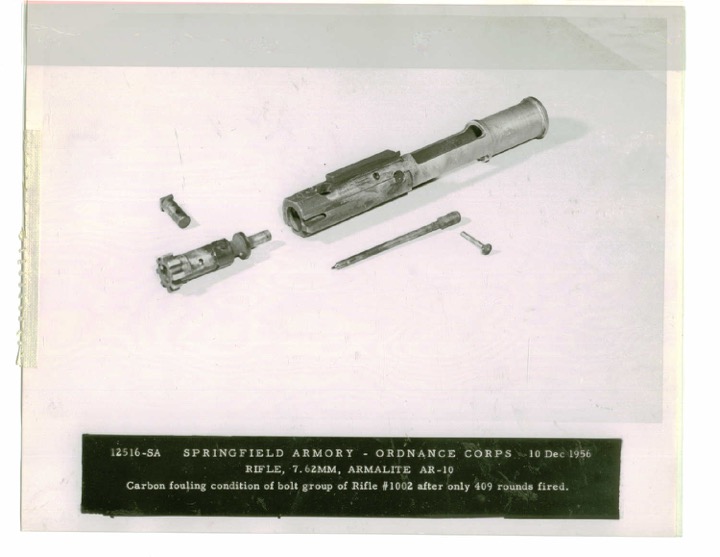

AR-10 Bolt

AR-10 Bolt

THE RIFLE OF THE FUTURE TAKES SHAPE

In 1955 the first prototype of the AR-10 came to birth, but it didn’t last long: it was actually closer to a modified Johnson Machinegun than the AR-10 that we know, having the same sights, the same tubular stock and using a Browning BAR magazine, feeding .30M2 (30-06) cartridges.

At the end of 1955 a second new prototype was developed, with all-around new features: the stock was a triangular-shape full piece made out of plastic and fiber glass, the material was used for the handguard and the pistol grip, the sights were replaced with a German ZF-4 optic and the magazine was substituted with a dedicated aluminum to feed the new 7,62 NATO (.308 Winchester) cartridge.

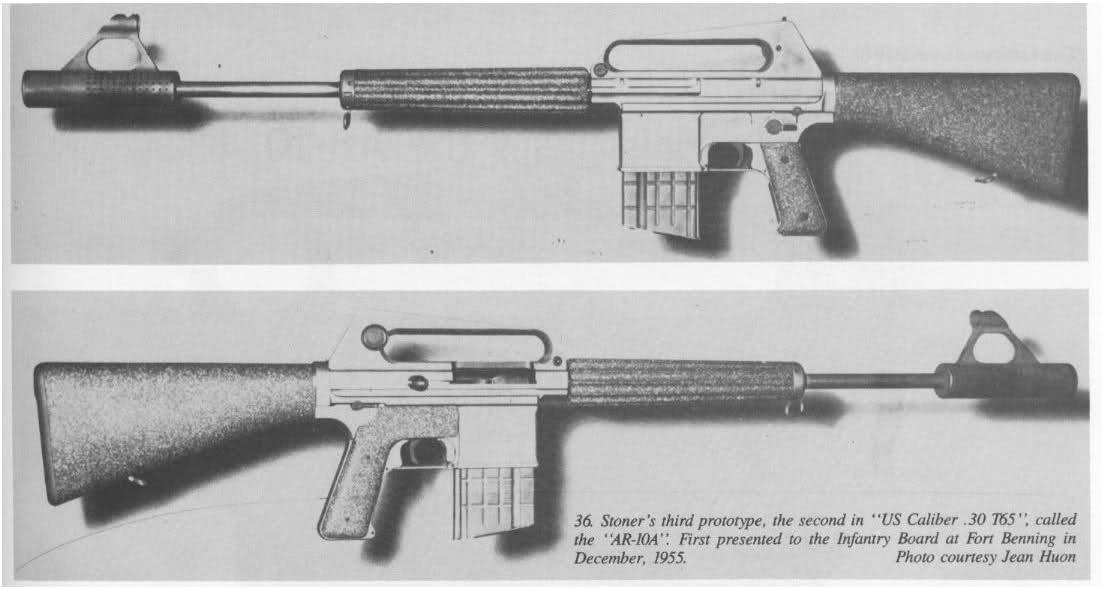

In December 1955 a third prototype came up, denominated AR-10A. This new rifle went back to the iron sights, the rear sight was now enclosed in a protective carry handle placed above the receiver while the front sight was placed in a new delta shaped structure above a muzzle device. The muzzle device was a two-pieced cylinder made of duralumin, that was an excellent flash hider and muzzle brake.

This last prototype was presented to the CONARC (Continental Army Command) to run in the trials for the new american infantry rifle. The AR was well received but the CONARC decide to keep the focus on the T44 and T48 models (the two prototypes of the future M14 and FN FAL rifles) which were already way further developed than the AR.

Even if the first trials were a failure for the AR-10A, the CONARC would promote the AR-10A into the SALVO program. The SALVO program, late evolving in the SPIW program, was launched to research and develop the new concept of a high velocity small caliber cartridge: from this program will be developed the AR-15, adopted as the M16, chambering the new .223 Remington cartridge.

AR10-A

AR10-A

In 1956 ArmaLite offered Fairchild a fourth prototype, the AR-10B, recognizable by the charging handle now placed under the carrying handle, substituting the previous one mounted directly to the bolt carrier. A new front sight was added, built separately from the muzzle device.

AR-10B

AR-10B

Before going on, we have to stop to think about the characteristics that made the AR-10 such a modern rifle: the large use of polymer and aluminum, matched up with the muzzle device and the direct gas system made it an exceptionally lightweight rifle but still very controllable.

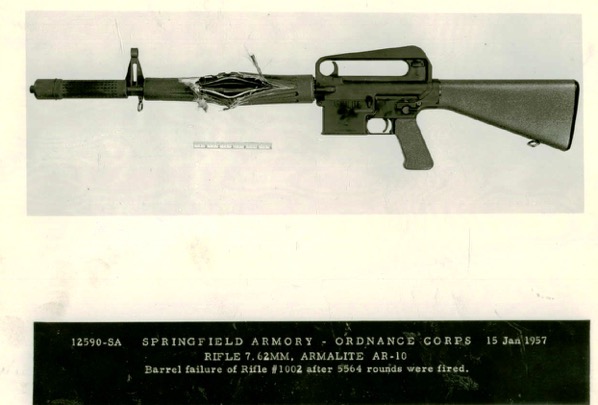

In December 1956 the AR-10 was again submitted to the CONARC for trials, but it didn’t perform well:

the rifle was sensitive to dirt and cold weather, witnessing various stoppages, failure to feed and extraction; specially when at temperatures below 0°C (+32°F). Another major issue was the muzzle device, that showed to be fragile. In January 1957 the tests went back on two new rifles (serial numbers 1002 and 1004) with a new muzzle device in titanium instead of duraluminum. The problems related to the cold temperatures continued to appear and, most importantly, the serial number 1002 exploded in a catastrophic failure of the barrel, that up to this moment was made out of aluminum with a steel liner. Quickly Stoner modified a couple of barrels from the T44 prototypes, and came back for new trials, but the malfunctions continued to show up.

At this point the Pentagon was waiting for new reports, and so the CONARC could only close the trials and send the results.

That was not seen well from the military point of view, which was still deeply focused on heavy and rugged rifles made of steel and wood, that had to be capable of mounting bayonets and rifle grenades (two elements that were purposely left behind during the development of the AR-10). In February 1957 the AR-10B was declared not viable for military use, and so, discharged from further testing.

Later the same year, the US Army would choose the T44 as the new standard infantry rifle under the name of US Rifle, 7,62mm, M14.

ARMALITE LANDS IN EUROPE

The adoption of the M14 by the US Army wasn’t taken just as a disappointment by Fairchild. The company had spent a huge amount of money and work to develop the rifle and the idea of just giving up with the project wasn’t even considered. We have to remind that ArmaLite had developed a larger family of rifle from the AR-10: it included a dedicated sniper/marksman variant, carbine/smg short barreled rifle, and a fully developed light machine gun that could have served as a multi-purpose machine gun mounted on a tripod with a separated ammunition container. Fairchild was looking for expand itself, licensing the production of the rifle in the idea of, at least, getting some contracts in the smaller countries that had not yet adopted a rifle chambered in the new NATO cartridge.

Around that time Fairchild was dealing with the Dutch Fokker to license the production of airplanes, and was Boutelle himself to discover that the Netherlands had not adopted a rifle in 7,62 NATO. The rights of a full scale production were acquired totally by the Artillerie-Inrichtingen arsenal, sited in Zaandam, outside Amsterdam. The arsenal was positive that the Dutch army would have adopted the rifle if the necessary changes would have made, and so had spent 2 million dollars to tool up the production line.

In the same time ArmaLite hired a new engineer, James Sullivan (not related to the founder George Sullivan), wich was commissioned to came up with the modifications needed for production.

LAUNCHING FULL SCALE PRODUCTION

Before starting this new paragraph, we have to make clear that for the AR-10, the gun collecting community had divided its main variants produced by the A.I. arsenal in three main categories: the Sudanese, the transitional model, and the Portuguese.

Top: Portoguese AR-10 / Bottom: Sudanese AR-10

Top: Portoguese AR-10 / Bottom: Sudanese AR-10

James Sullivan started working on the AR-10, mainly converting the blueprints from the inch system to the metric system, but also trying to make it easier and cheaper to produce, as well as making the changes necessary to stick with the Dutch army standards. The updates included a new front sight, with a different gas port and gas block, the gas tube was moved from the left side to the 12 o’clock position (as we can see it nowadays in the AR-15 series of rifles), and a muzzle brake capable of launching rifle grenades.

This pattern of AR-10, also known as ‘Cuban’, was offered to the Cuban government of Batista, and got a first order for a hundred rifles. But while this batch of guns was in production, Batista was taken down by Castro and the rifles weren’t shipped. At this point Interarms, the company in charge of selling the rifles, reached for a second time to the new Cuban government, wich tested the AR, like it and placed a second order, stopped by the US embargo on Cuba.

Other countries were interested about the AR:

The Italian navy elite unit COMSUBIN showed interest for the rifle. Even though was too expensive for the Italian state coffers, the special units were economically independent when choosing their equipment. In January 1962, the Ministry of Defense ordered 60 AR-10 and 3 optics for a total of 10.446,10 dollars for the unit. It’s interesting to note that this was the last order and the last batch produced by the Artillerie Inrichtingen.

Italian special forces COMSUBIN with AR-10 NATO/Portuguese

Italian special forces COMSUBIN with AR-10 NATO/Portuguese

Below are the some pictures of the operator’s manual for the optic made for the Italian army

(pictures thanks to ar10.nl)

Nicaragua ordered 7500 ARs, but the order was rapidly cancelled after one of the trial rifles exploded right in the hands of the general Somoza during a test.

Guatemala ordered 500 rifles with the only recognizable change being a barrel shroud. Along with other South American countries that aquired some rifles for trials, but none resulted in a major order.

Finland asked for a test variant in 7,62x39, with the aim of finding a new service rifle chambered in the soviet ammunition.

Finally when A.I. was ready for starting full scale production got it first major order. In 1958 Sudan became independent, and was so trying to build up a modern army, capable of dealing with the nearby Egypt and the internal disorders. Due to the shortage of L1A1 rifles, which were favorite, the AR-10 was chosen: 2500 were ordered. The rifles needed to be slightly modified to comply with the army requests, and so the Sudanese model was born: basically a ’Cuban’ variant, with an added barrel shroud capable of mounting bayonets; a muzzle brake threaded to use a muzzle booster for shooting with blanks; the sights were improved with tritium dots for shooting in low light conditions; a brass disk was added to the stock to put in the unit markings; and for few examples a 3x25 optic was issued along with a dedicated cut on the carrying handle. Another particular of the Sudanese are the markings on the elevation drum, which are in Eastern Arabic instead of the Western Arabic numerals. Both the Cuban and the Sudanese rifles still have the ‘SAFE’ position on the selector placed in the upward position, and the charging handle is not telescopic, which means it sticks out of the upper receiver when pulled backwards.

This rifle was basically a slightly modified AR-10B, with pistol grip, stock and handguard made of plastic. The structural features remained the same, and that’s why we call the Sudanese the first one, even though the Cuban came earlier.

Below more pictures of a Sudanese AR:

At the end of the article there are more detailed pictures about the differences between the Sudanese and the Portuguese.

In the transitional model the trigger group components were changed, placing the SAFE position where we know can find on an AR-15 (the same happened for the very first AR-15s, which had a lot in common with the AR-10s) and a spring to the trigger was added; the barrel was replaced with a standard barrel, not lightweight anymore, capable of launching rifle grenades and an improved handguard was made with wood and stamped sheet metal.

The transitional model was also made in different variants: a bipod ready belt fed machine gun, a short barrel carbine and a infrared scoped sniper variant, with the carrying handle modified like in the Sudanese.

Transitional Model

Transitional Model

The Portuguese model was developed in 1960 during the trials for the new service rifle in the new state of South Africa. The new features are a telescopic charging handle, and an integrated bipod. The Portuguese model is the one taken as example in this article, imported in the italian civilian collectors market after a demilitarization process.

The AR-10 was tested along with other rifles chambered in the NATO cartridge (those were a CETME, a G3, a FN FAL, a Stg57 and a Madsen Light Automatic Rifle) and came second, after the FN FAL, ending the chances of a Dutch contract: in 1961 the Dutch government, looking at the result of the tests, would chose the well proven FN FAL.

But a nation was still looking for the Ar-10: Portugal.

Portugal had received a few rifles, and a small batch was ordered for his special units, and was looking to issue the whole army with its last variant, what we call nowadays ‘the Portuguese’. At the time Portugal was still fighting the communist uprisings in his african colonies, mainly in Angola and Mozambique.

THE HISTORICAL BACKGROUND OF THE PORTUGUESE AR-10

During the 60s Portugal found himself dealing with an expensive and hard war to maintain his African colonies. Salazar’s authoritarian government tried every possible way to keep it’s empire overseas, even if economically the nation wasn’t capable of sustain such a high expense necessary to ensure military control over the colonies. The two main war theaters were Angola and Mozambique. Here the insurgents, supported by the Soviet Union, China and Cuba with weapons and military advisors (mainly Cubans), engaged a long and harsh war that lasted up to 15 years, when in 1974 the independence was obtained. The victory of the rebel factions was more a consequence of the falling Portuguese government than a victory on the battlefields. The transition to a new military government, followed by Mario Soares’ socialist government, were crucial to the decolonization war. Portgual ,at this point exhausted and lacking in resources couldn’t maintain such a big, for the small Portugal, military contingent overseas.

On the ground both Mozambique and Angolan liberation forces fought a fierce war, with wearing guerrilla tactics, against the Portuguese troops. Although in superior numbers to the Portuguese troops, the rebel factions were deeply divided internally: those division led to numerous battle and clashes between the insurgents units. This situation kept the war in a stalemate for 15 years, where neither one of the factions could gain terrain over the others. Since the 60s Portugal started recruiting, in its overseas units, more and more African volunteers (which were usually just looking for a wage to maintain the family) to swell the increasingly small portuguese special units. Even if Portugal was already a NATO member it didn’t receive any sort of military help or guns from other member states, that saw the war for the colonies, with growing disapproval because of the atrocities committed.

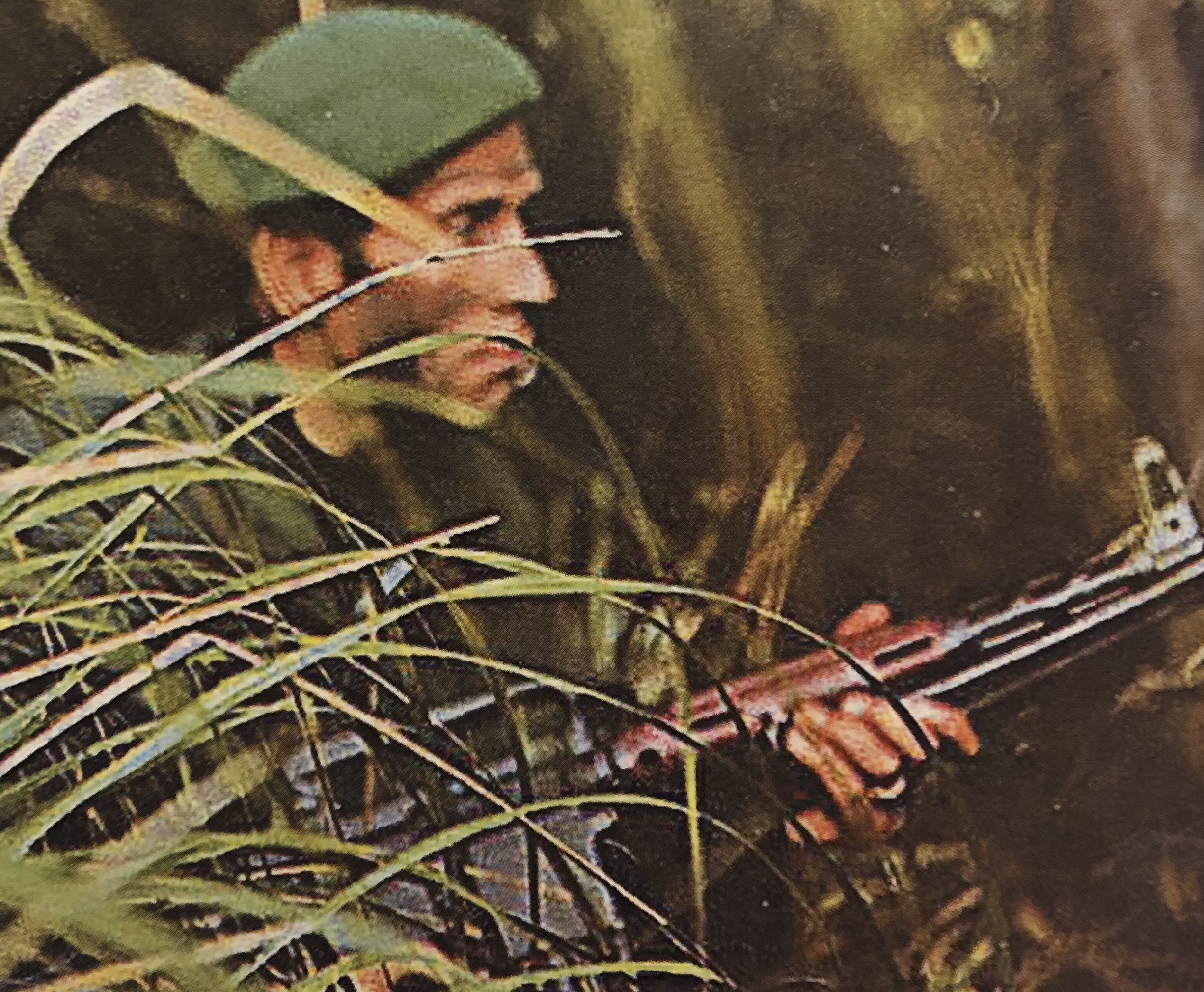

In fact, only a few thousand of AR-10 (estimated from 1000 to 4000) reached the troops in the colonies, before the Dutch government issued an embargo on arms sales to Portugal. The rifles delivered were barely enough to arm two of the four battalions deployed in Africa. This order was the biggest ever but obviously wasn’t enough to keep the production of AR-10s alive, and in 1961 Artillerie Inrichtingen shut down the production. All the spare parts necessary to the maintenance of the rifles were produced directly in Portugal during the 15 years to come. The procurement of firearms and vehicles become even harder and some help was sent by Rhodesia and South Africa, which saw in the communist uprisings a menace to their government. This kind of logistic and military help allowed Portugal to face, up to 1974, the rebel troops growingly aided from the Soviet Union and Cuba through the nearby nations. Thousands of Cuban military advisors, took part in the fighting in Angola. The fighting lasted up to 1974 when, as we briefly discussed earlier, the new military government decided to disengage permanently from all the overseas possessions.

Angola: Portuguese army with AR-10

Angola: Portuguese army with AR-10

FEATURES AND ACCESSORIES

Bayonet:

The Portuguese bayonet is atypical and don’t resemble any seen model, with a double blade, differently from what is usual, it mount on the upper side of the barrel, not downside. The holster is similar, but not identical, to the American M8 model. The marking ‘AI’ can be found on the blade.

The model shown is a reference only to the Portuguese model, the Sudanese bayonet model is different.

Below is a picture of the Sudanese bayonet, made in Germany by Interarmco.

This bayonet originate from german SG42 bayonet. Inside handle there is a multitool.

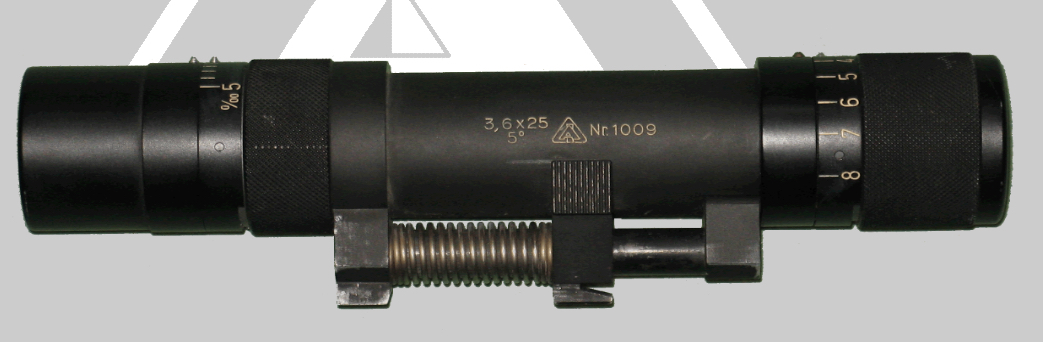

Optic:

From Artillerie-Inrichtingen came out a dedicated 3.6x25 optic. This optic couldn’t be mounted on every AR-10, because a specific set of cuts must be made on the carrying handle. Fortunately, we have also pictures that prove its use in Africa.

Bipod:

A dedicate version of the AR-10 existed with the bipod. A specific handguard, cut to make room for the bipod, was necessary as not every AR-10 could mount it.

Comparative gallery between the Portuguese and the Sudanese models:

On the left of the stock and buttpad of the Portuguese with the lateral sling swivel and without the cleaning kit port.

The Sudanese has a cleaning kit port and the brass disk is noticeable, in which the unit number were written.

Front and rear sights: the Sudanese on the right has the night sight dots and the elevation drum with eastern Arabic numbering.

Telescopic charging handle of the Portuguese on the left, and fixed charging handle of the Sudanese on the right.

First type selector switch for the Sudanese AR on the right, NATO pattern selector swith for the Portuguese on the left (like later AR-15/M16).

(Up) Barrel sleeve with bayonet lug and three prong flash hider threaded to mount muzzle booster, for blank firing (Sudanese pattern).

(Down) Grenade launching capable barrel, with built in flash hider and bayonet lug (Portuguese pattern).

Because of the grenade launching capabilities, the Portuguese AR has a dedicated adjustable gas block, that can be opened or closed.

CLASSIFICAZIONE COLLEZIONISTICA:

PORTOGHESE:

| Rarity | 4 |

| Historic Value | 3 |

| Rarity likely to increase | 3 |

| Value | 3 |

| Condition | GRADE B+ |

SUDANESE:

| Rarity | 5 |

| Historic Value | 3 |

| Rarity likely to increase | 4 |

| Value | 5 |

| Condition | GRADE B+ |

For Scoring Table, click here

VIDEO:

CLICK HERE to see our firing test

Copyright©2019 - Christian Gorr e Daniele Belussi per CoEx

Thanks to Ar10.nl

Historic content David Elber

Translation in english Kevin Fisher

To Gallery CLICK HERE (italian article)

condividi: